If the crocodile cares when a tourist throws a coconut at him from the Rio Grande de Tárcoles bridge, his face betrays nothing. He lunges and snaps instinctively, but promptly discards it, coconuts being among the few things an American Crocodile won’t eat.

Still, there is no trace of disappointment in his reptilian eyes, no sigh like annoyance in the breath he may surface to draw only once every hour, nothing spiteful in the way his back scales (called scutes) ripple muddy water, patiently circling. For all humanity throws his way, the crocodile remains inscrutable.

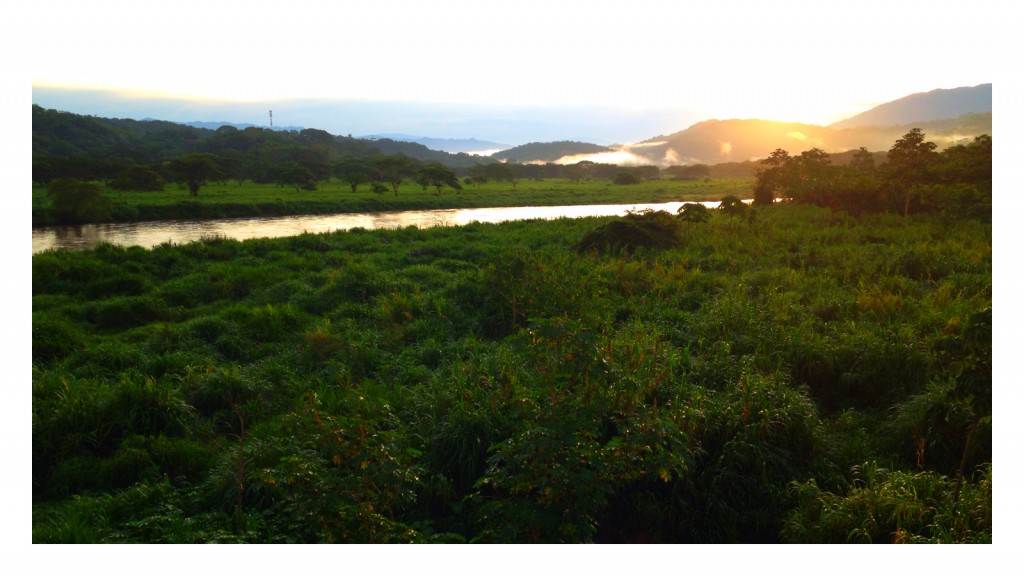

By now, the American Crocodiles that hang out under this famous bridge in the Pacific Central region of Costa Rica are accustomed to diverse offerings from above, some tasty, some inedible, all launched by humans who stop to gawk from the relative safety of the bridge. Near this aerial viewpoint, the entrance to Carara National Park offers access to primary rain forest, waterfalls and ideal crocodile habitat, just a few minutes drive from Jacó. Biologists estimate more than 2,000 crocs inhabit parts of the Tárcoles River basin, a system that flows all the way from the volcanic highlands near our Coronado campus to the coast near our Jacó location.

Since it is World Environment Day and crocodiles are pretty timelessly fascinating, we decided to take a little extra time on our way between schools to loiter on the bridge connecting our campuses and consider one of Coast Rica’s most ancient predators, both fearsome and fragile in today’s world.

The average adult male crocodile is 4.3m (over 14 ft) long. He can live 70 years. His diet consists primarily of fish, but can include pretty much anything fleshy that crosses his path, coconuts excepted. He does not rely solely on eyes or ears to find food, but can sense its precise location using dome receptors — little black dots visible around the sides of his jaws. This sixth sense is a fortunate adaptation for the Tárcoles crocs, who may be literally blindsided by climate change.

Lately longtime observers of the river have noticed increasing cases of blindness in adult male crocodiles. Scientists initially hypothesized that contamination from cities and farms must be causing some kind of blinding infection. However, initial investigations (i.e. five people capturing, hog-tying and sitting on 1,200 lb. crocs while a veterinarian warily checks the eyes), revealed that blunt trauma is a more likely cause than pollution. It appears only adult males are going blind, seemingly due to gnarly injuries sustained in fights with other adult males.

Meanwhile, the gender dynamics of the Tárcoles croc population are changing. Where there used to be about three females for every male, now it’s more like 1:1. Theory goes, the decline of a female-dominated society is leading to more eye-poking feuds between males during mating season.

But why the sudden uptick in male crocodiles?

The sex of a crocodile is determined by temperature: the warmer the nest, the more the males. Leading crocodile experts believe that climate changes, particularly localized effects caused by deforestation in the Tárcoles basin, are causing warmer temperatures in the crocs’ nesting habitat. Less trees may mean more male crocodiles, more fighting over female crocodiles, and eventually, no female crocodiles at all.

From the Tárcoles bridge our coconut-throwing kind might imagine these enormous reptiles are living much as they did in the age of dinosaurs. However, rapid environmental changes instigated by humans are in fact changing their reality, perhaps disastrously. We scan the muddy banks of the river, looking for females jealously guarding nests dug into verdant cover. The babies will be born soon, entering the world with the first heavy rains. At first nurtured as a tight-knit clan by a protective mother, at five weeks they are capable of hunting insects and small fish and will eat each other should the pickings get too slim.

Sea turtles are less famous for this kind of unapologetic survivalism, but like crocodiles develop with temperature-dependent sex determination and face possible extinction by climate change, in addition to habitat destruction. Programs exist on both coasts to bolster turtle conservation efforts, for which our students routinely volunteer.

-Emily Jo Cureton